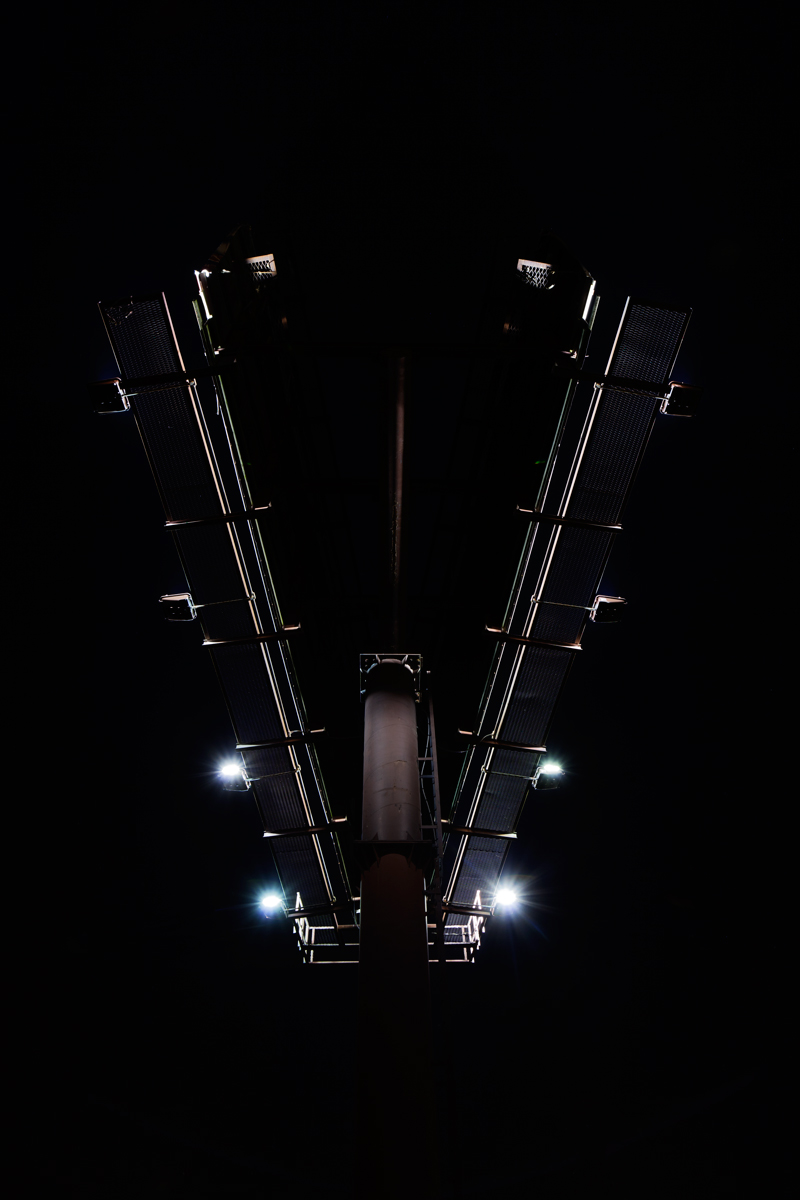

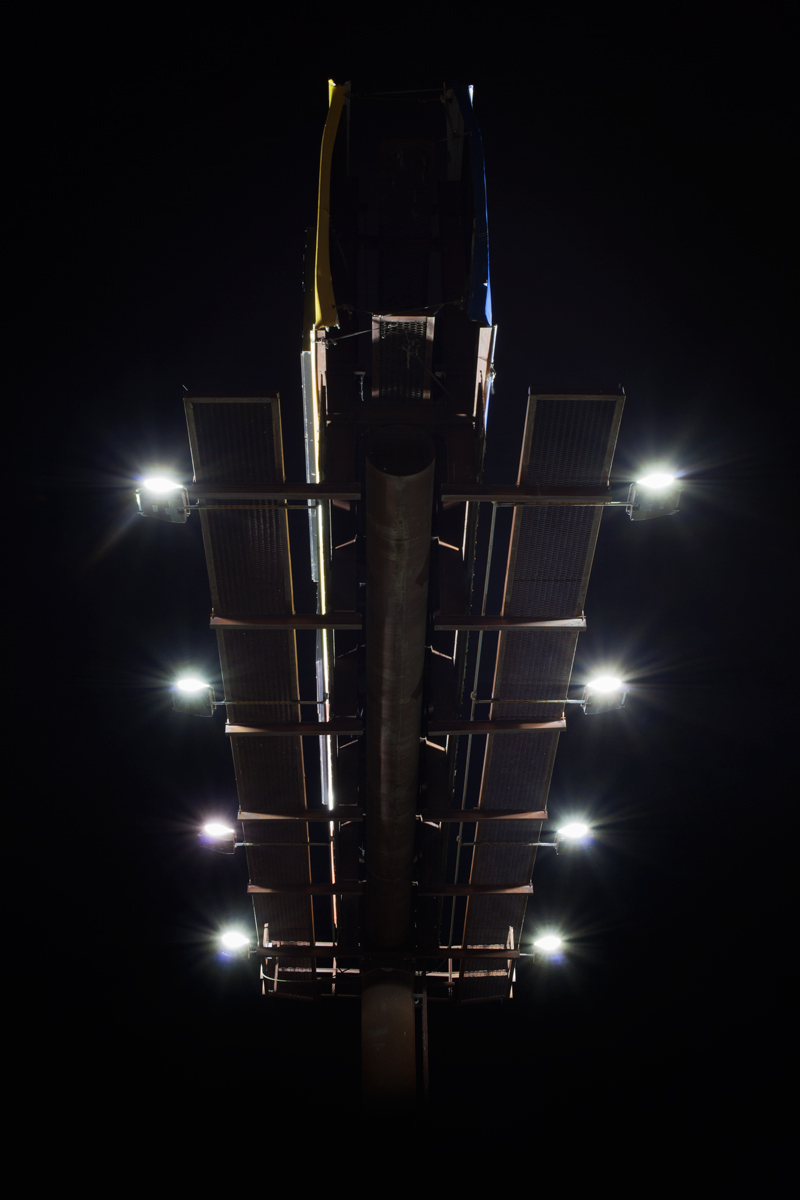

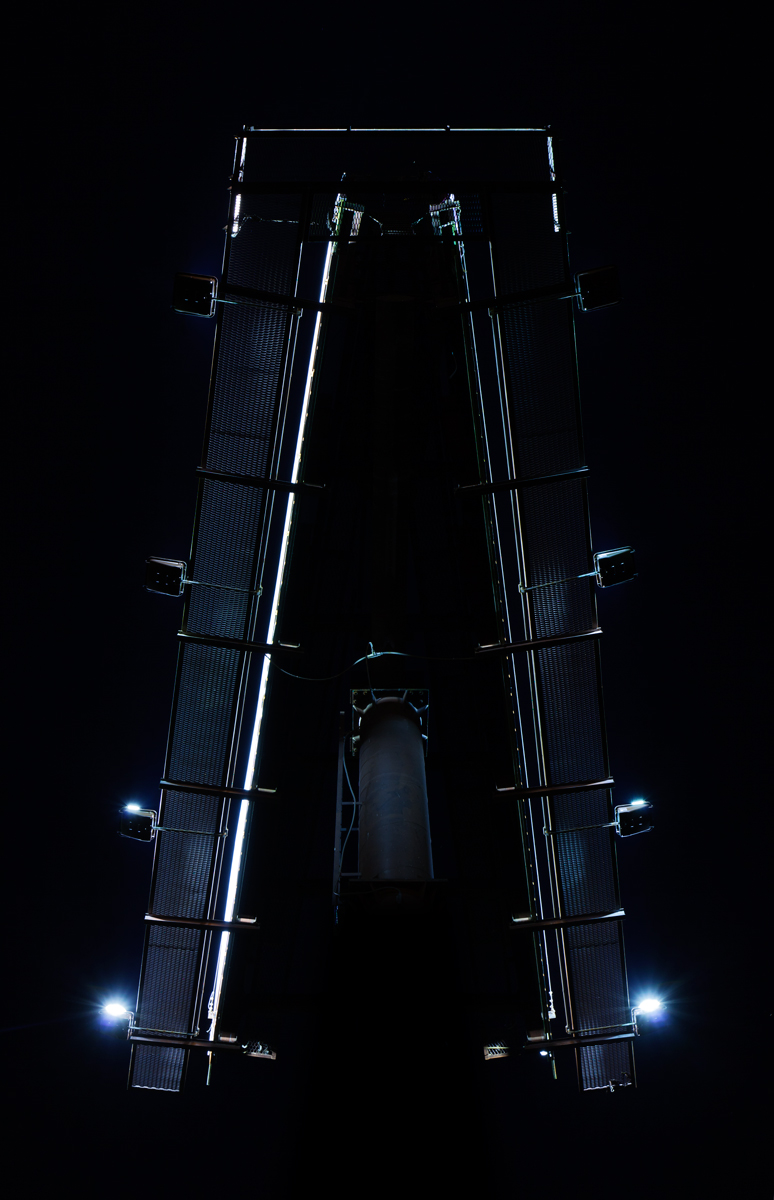

Images By: Stephen Chalmers

Written by: Ryan Nemeth

A city can be defined as a large and permanent human settlement that is a hub of population, commerce and culture. Thus, cities have always functioned as resource centers for human beings and it follows that modern civilization is deeply intertwined with urban activity. In fact, many of the world’s great universities, libraries, cathedrals, and museums are the result of human collaboration and innovation enabled by urban environments. Make no mistake that humans have readily picked up on the explicit and implicit benefits of life in the city. This is evidenced by humans’ massive migratory shift from a predominantly rural existence to one that is largely urban. At the turn of the nineteenth century, just two percent of the world’s one billion human inhabitants lived in cities. As of 2015, nearly 60 percent of the world’s 6.7 billion people currently live in cities. By 2050, this number is projected to be as much as 75 percent of the world’s 8.5 billion inhabitants. Given this statistic, one might easily assume steady global growth patterns for cities both large and small. However, something entirely different and somewhat paradoxical is happening.

Many cities are demonstrating significant population declines as others continue to thrive and grow. In fact, between 1950 and 2000, as many as 350 large global cities showed significant or stagnant declining population growth rates. Better yet, during the 1990s, more than a quarter of the world’s large cities receded. What is more surprising is that these trends seem to be prevalent in countries with expanding economies. Countries such as the USA, China, Germany, Japan, Korea, Finland, Belgium, Italy and Russia have noted recent and significant downward growth trends peppered throughout urban centers. In many cases, these numbers are driven by changes or events that challenge the utilization of human capital. For example, in Eastern European countries and China, new labor and migration patterns have been driven by the introduction of capitalist economies. Here in the States, our transition to a service economy has heightened labor migration. The truth is that the rationale for the global “Shrinking Cities” phenomenon remains varied, however, many of the symptoms and ills associated with contraction are quite similar irrelevant of geography. Although these global declining growth patterns have long been identified, a 2002 German project creatively titled "Shrinking Cities" was the first to coin the term explaining this worldwide trend.

The “Shrinking Cities” project was initiated by the German Federal Cultural Foundation and the architecture magazine Archplus in response to shifting migratory patterns in Germany. More specifically, the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989 led to more than a million empty apartments and to the abandoning of countless industrial parks and social and cultural facilities in Eastern Germany. Thus, the “Shrinking Cities” project was initiated as an attempt to research and understand key drivers and relevant solutions to urban decline within Germany and abroad. Outside of Deutschland, the Shrinking Cities International (SCI) project gathered four interdisciplinary teams to study shrinking cities abroad, these cities include: Detroit, Mich.; Manchester and Liverpool, England; Ivanovo, Russia; and Halle and Leipzig, Germany. The broader research gathered by the SCI has led to insightful discoveries and collaboration while precipitating more activity on the topic of urban shrinkage. Here in the States, urban studies researchers, including those at the Institute of Urban and Regional Development at the University of California, Berkeley, have followed suite by creating a “Shrinking Cities” group of their own.

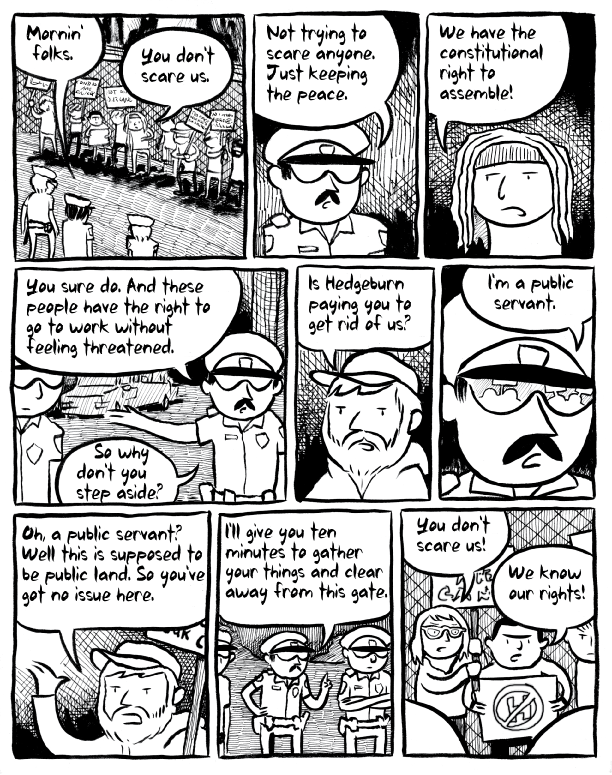

It is important to note that the “Shrinking Cities” concept contradicts the traditional industrial “Boomtown” image of a big city that is characterized by constant economic and demographic growth. Shrunken cities often spur a reconsideration of the economic, social and cultural benefits that serve as human attractors to the modern city. In many cases, people simply leave as opportunities and city resources diminish. To date, many cities with “Shrinkage” have demonstrated resistance to traditional urban planning solutions as the fixes go well beyond simply creating new jobs and reallocating resources. Many shrinkage dilemmas are driven by widespread resource constraints that spill over into social and cultural issues within the urban core and municipality. What follows from the scarcity often yields environments whereby there are competing and conflicting interests for highly limited resources. Furthermore, and most importantly, these limitations are forcing planners and municipalities to allocate their services in unfamiliar environments and under new and challenging circumstances. As new cities arise from the ashes, shrinking municipalities will increasingly be forced to serve community needs with non-traditional methods utilizing creative solutions. This need for adaptation has proved to be a very tough proposition for many municipalities. In the case of Youngstown, OH and Detroit, MI, city planners have lagged well behind their stated goals and intentions for cleanup.

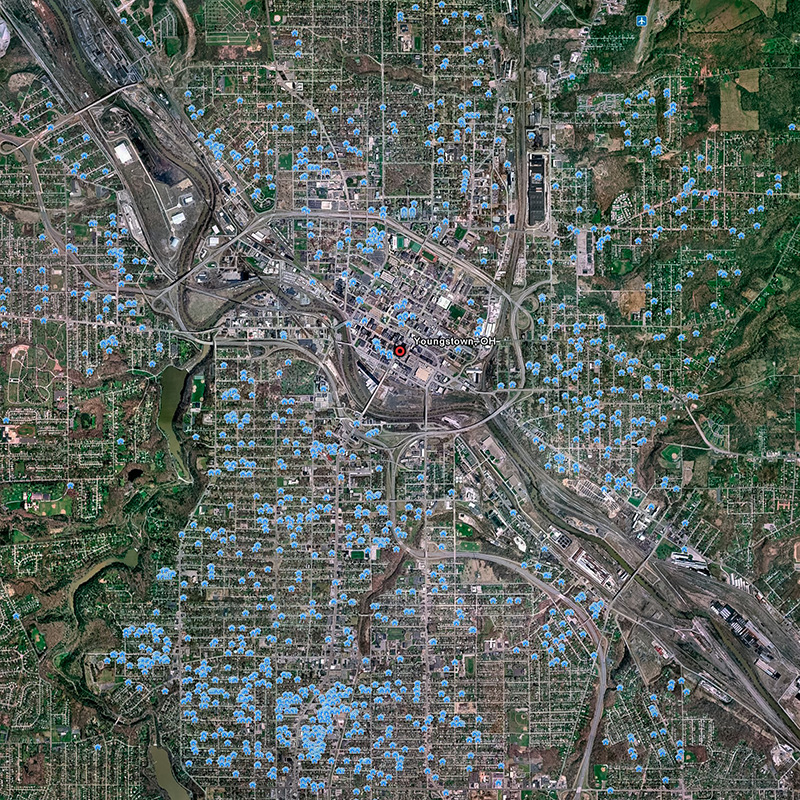

Most Americans will probably find it surprising to know that one in ten U.S. cities are currently experiencing stagnate or declining population growth. However, it should be no shock that the earliest urban deflation events are often attributed to the effects of deindustrialization and or globalization. Thus, it is fairly easy to understand why single industry manufacturing towns started taking it in the chin as early as the 1950s. One town in particular that has suffered tremendously from the effects of deindustrialization is Youngstown, Ohio. Youngstown was named America’s fastest shrinking city as of the 2010 census. The city is located in Steel Valley between Cleveland, OH and Pittsburg, PA and once upon a time it was one of America’s great steel producing towns. Youngstown has suffered tremendously from its growth as an economic monoculture where steel dominated employment opportunities and most of the local economy. Between 1960 and 2010, Youngstown lost 60% of its population, deflating from a city of 170,000 residents to a town of 67,000. Not surprisingly, as of the 2010 census, Youngstown was recorded with the highest percentage of residents living in concentrated poverty and one of the highest violent crime rates in the nation. In 2006, the city reported the demolition of 2,566 structures. As of 2010, it was estimated that there are another 6,000 (GIS estimate) vacant buildings located within the 34 square miles of the city limits.

As early as 2002, the city of Youngstown began enacting a plan for cleanup and preservation that was later unveiled as the Youngstown 2010 Plan. The 2010 plan was a pioneering effort in "smart shrinkage", which was targeted investment to relocate people from areas of the city with high numbers of vacancies to more viable neighborhoods. The enacted plan would have created a spacious grid for an estimated 80,000 residents, however, the plan proved to be illusory. Since the unveiling of the plan in 2010, the city has lost another 15,000 residents; the poorest and most blighted parts of the city are still predominately black and the most prosperous and stable areas are still white; block watches and neighborhood groups are filling the gap left by an absentee local government; urban farms are popping up among the vast tracts of vacant land in the city and community and cultural groups are still struggling to make change happen. All provide evidence of a much larger breakdown in the governance and function of the municipality. In his seminal 1992 book, about the former steel town of Homestead, Pennsylvania, William Serrin wrote, "America uses things; people, resources, cities and then discards them." Could it be that this statement sufficiently explains a larger reality for many small towns and cities around the globe like Youngstown, OH, that are experiencing urban shrink? As the function, utility and quality of life is challenged in these places it is evident that we can no longer just abandon ship.

Stephen Chalmers earned his MFA in Cinema and Photography from Southern Illinois University. He was the NW Regional Chair for the Society for Photographic Education for two terms, a professor of Photography and Digital Media in the state of Washington for eight years and is currently a professor of Photography at Youngstown State University in Ohio. His series Youngstown, OH documents the “Urban Shrinkage” that has transpired in his hometown of Youngstown, OH.

You can find more from Stephen Chalmers here: http://www.askew-view.com

References:

- http://enviroliteracy.org/land-use/urbanization/

- Reference 2

- Reference 3

- http://www.huffingtonpost.com/the-groundtruth-project/how-youngstown-ohio-becam_b_5671919.html

- Tavernise, Sabrina (December 19, 2010). "Trying to Overcome the Stubborn Blight of Vacancies". The New York Times. Retrieved November 30, 2012.